Link to Video:

http://www.theguardian.com/science/video/2014/apr/01/robotic-exoskeleton-world-cup-debut-video

Shortly before 5pm local time on 12 June at Arena Corinthians in São Paulo, a young paraplegic Brazilian will stand up from a wheelchair, walk over to midfield, and take the first kick of the 2014 World Cup.

For those hoping for miracles at football's greatest tournament, the scene may be the closest they get to witnessing one. For Miguel Nicolelis, a neuroengineer based at Duke University in North Carolina, the moment demands faith of another kind. As hundreds of millions tune in for the opening match, they will see the first public demonstration of technology he claims will turn wheelchairs into museum pieces.

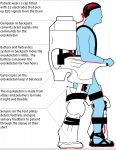

The technology in question is a mind-controlled robotic exoskeleton. The complex and conspicuous robotic suit, built from lightweight alloys and powered by hydraulics, has a simple enough function. When a paraplegic person straps themselves in, the machine does the job that their leg muscles no longer can.

The exoskeleton is the culmination of years of work by an international team of scientists and engineers on the Walk Again project. The robotics work was coordinated by Gordon Cheng at the Technical University in Munich, and French researchers built the exoskeleton. Nicolelis's team focused on ways to read people's brain waves, and use those signals to control robotic limbs.

On Tuesday, the team launches a Facebook page that will document the project in the days leading up to the World Cup. A dedicated website is due to go live later this week.

Nicolelis is training nine paraplegic men and women, aged 20 to 40, to use the exoskeleton at a neurorobotics rehabilitation lab in São Paulo. Three will be chosen to attend the opening game between Brazil and Croatia, with one volunteer heading on to the pitch to perform the demonstration.

To operate the exoskeleton, the person is helped into the suit and given a cap to wear that is fitted with electrodes to pick up their brain waves. These signals are passed to a computer worn in a backpack, where they are decoded and used to move hydraulic drivers on the suit.

The exoskeleton is powered by a battery – also carried in the backpack – that allows for two hours of continuous use.

"The movements are very smooth," Nicolelis told the Guardian. "They are human movements, not robotic movements."

Nicolelis says that in trials so far, his patients seem have taken to the exoskeleton. "This thing was made for me," one patient told him after being strapped into the suit.

The operator's feet rest on plates which have sensors to detect when contact is made with the ground. With each footfall, a signal shoots up to a vibrating device sewn into the forearm of the wearer's shirt. The device seems to fool the brain into thinking that the sensation came from their foot. In virtual reality simulations, patients felt that their legs were moving and touching something.

One patient, whose spinal injury meant he could not feel or move his legs, told Nicolelis: "I feel like I'm walking on the beach, that I'm touching the sand."

Nicolelis likens the effect to the rubber hand illusion, where the mind is tricked into thinking that an inanimate object is part of the person. "It confirms our prediction that we are going to elicit a sensation that the exoskeleton is an extension of their body," Nicolelis said.

In other trials, patients have used the mind-control system to walk on a treadmill.

Nicolelis said he believed the technology was ripe for turning into everyday devices to help paraplegics and could ultimately replace wheelchairs.

"All of the innovations we're putting together for this exoskeleton have in mind the goal of transforming it into something that can be used by patients who suffer from a variety of diseases and injuries that cause paralysis," he said.

The system has been through numerous safety tests. The exoskeleton is fitted with multiple gyros to stop it falling over during the balancing act of bipedal walking. As an extra safety measure, it was fitted with multiple airbags.

Last month, Nicolelis and his colleagues went to football matches in São Paulo to check whether mobile phone radiation from the crowds might interfere with the suit. Electromagnetic waves could make the exoskeleton misbehave, but the tests were encouraging. The chances of the exoskeleton malfunctioning, and stomping off into the distance, are apparently slim.

Sethu Vijayakkumar, a roboticist at Edinburgh University, said exoskeletons were a natural progression for rehabilitation and made the most of robotic and human abilities.

"This is something that will happen, and needs to happen. Humans are very good at high-level decisions and making sense of ambiguous situations, but robots are very good at very precise, repetitive, accurate movements," he said. "Exoskeletons are the way to marry these two together."